(A paper given to a Presbyterian Scholars Conference

at Wheaton College, Wheaton IL, 19 October 2016)

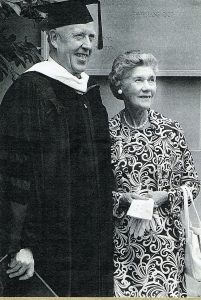

Forty years ago a Canadian academic, Presbyterian minister William Stanford Reid, Professor and founder of the History Department of the University of Guelph, delivered the address at the 116th commencement of Wheaton College. “Facing A Secular World” was his title and it was an apologia for thirty-five years as a Christian academic in two of Canada’s leading post-secondary institutions, the historic McGill University in Montreal and the new University of Guelph where he was a founding faculty member. At 62 years of age he was at the peak of a successful career, climaxed by the appearance two years previously of what he hoped would be his crowning literary achievement, a biography of the Scottish Reformer John Knox.

His speech that day was vintage Stanford Reid, demonstrating his ability to hold an audience with telling anecdotes drawing on his thirty-five year experience as an academic, his humorous asides, but above all his strong Christian convictions. These he had fearlessly maintained in an environment quite different from Wheaton. He was also a Canadian, so there was a double disconnect. In spite of this – or perhaps because of it – Stanford Reid held his audience since the topic bridged those two divides. Titled “Facing A Secular World,”[1] Reid spoke with grace and authority of the world that those receiving degrees that day would face on graduation. It was both timely and challenging.

“Secular” was used by Reid to describe the university where he taught – in contrast to the college where he was now being honoured. In doing so, as a mainline minister, he was very outdated, if not counter-cultural, in his approach to post-secondary education. In his Soul of the American University George Marsden notes that by the 1960s for many Protestant faculty the whole distinction between “secular” vs “Christian” appeared to be outdated. “While during the 1950s a number of significant voices were still talking about the role of the Christian in the university, by the 1960s such concerns were sounding passé.”[2] As always throughout his life, in making such a distinction, Stanford Reid was bucking the trend.

In contrast, for ghettoized Evangelicals, “secularism” was a new concept. 1976, according to Time magazine, was the “Year of the Evangelical.” Both candidates for the presidency were professing church-attending Christians. The long plunge into oblivion for mainline Protestantism, more observable today in Canada than even the United States, had only just begun. As a native Quebecker Reid watched as Canada lurched towards separation and ethnic tribalism. A separatist government in Quebec would win their first election that November, shocking the entire country. The original ferment of the 1960s, which facilitated the Reids’ departure from the province, had turned first violent and then soon the PQ’ists would be in control of the provincial government. McGill, once a bastion of Anglo colonial culture, was forced to acknowledge the change, increasingly become bilingual and accepting of the political realities of the time.

Reid’s had been a life of privilege and predictability. Growing up in the wealthy Montreal suburb of Westmount, his father a respected and establishment clergyman, his mother very much a product of the British Empire, his early life had been a series of achievements. Now, as Nobel prizewinner Bob Dylan reminded anyone who might be unaware, “the times they were achanging.” Secularism was taking the place of previously unassailable religious convictions. This was particularly evident in Quebec with the collapse of the moral authority of the once powerful and dominant Roman Catholic Church. Today Quebec is the most secular area of North America, a harbinger of, one fears, the future.

So Reid threw down the gauntlet, He had seen, first for fourteen years at McGill and then eleven (so far, three more to go) at Guelph a new generation increasingly untouched (and unreached) by Canada’s Christian past. To a safe Midwestern American audience, steeped in a Christian culture, this was a different and unrecognizable world. But Wheaton professor and Reid’s great friend Arthur Holmes, who was responsible for the invitation and his honouring, asked Reid to bring a challenge. Holmes’ The Idea of a Christian College had appeared the year before and marked out a clear path for the Christian educator, with a Christian worldview and with Biblical and theological studies at the heart of his or her teaching. And, Holmes argued, the starting point had to be historical[3]. The study of history was foundational to Christian experience and knowledge.

This was, of course, vintage Reformed thinking which Reid had acquired at Westminster Theological Seminary. He arrived on campus in 1935 to discover a whole new theological environment. His father had sponsored several of J. Gresham Machen’s forays into Canada[4], enlisting him as a fellow combatant against the Church Unionists of 1925. But W. D. Reid was more a product of the turn of the century United Free Church of Scotland and the theology of his mother, a former missionary to India to whom he was devoted, he characterized as “pietism.” It was Cornelius Van Til at Westminster who shaped Stanford Reid’s apologetic and gave him such a powerful voice in the academy.

Reid’s favourite course offering at McGill was History 410, “The Intellectual History of Western Thought Since The Reformation.” Posited as a series of questions, with appropriate excerpted readings, the final, fifteenth, one was “Modern Civilization in Progress or Decay?” which ended with a page from Martyn Lloyd-Jones’ Truth Unchanged, Unchanging. In an unpublished (rejected?) article in defense of Van Til he wrote: “When the author commenced teaching history in a ‘neutral’ university he found that going back to the presuppositions of various personalities and movements opened up history to his classes in a new and to them a very different way, which often led them to look at their own presuppositions.”[5]

Such fearless presentations of the Christian message prompted the occasional reaction. But only once, Reid claimed, did another faculty member ask for his resignation, a biologist who didn’t agree with Reid’s critique of his particular concept of evolution. His department head “merely said: ‘I would not discuss this subject with him any more.’”[6]

Reid was no stranger to disagreement or opposition. By the very fact that he went to Westminster Seminary he brought on his head the wrath of the hierarchy of the Presbyterian Church in Canada. Throughout his life he fought for confessional orthodoxy in his denomination. Indeed he regarded his calling – an important word for Reid – as bi-vocational. When he returned to Canada in 1940 after researching his Ph.D. thesis at the University of Pennsylvania, the General Assembly was in session and unexpectedly approved his reception and ordination. It was fortuitous: the vacancy caused by the sudden death of his father-in-law had left the pulpit of Fairmount Taylor Church in Montreal vacant and there was a desperate shortage of clergy as so many had become chaplains. Reid was admitted without debate or question.

Some in the denomination might later wish they hadn’t been so receptive. For the next half a century Reid became the outspoken voice and conscience of the denomination. At his own expense he published two broadsheets that appeared, usually monthly, for thirty years, theologically critiquing the church’s proposals, decisions and appointments. In a 7 September 1974 letter to Alex MacSween[7], a denominational functionary who had inquired, on behalf of an investigative committee, why he (and so many others at the time) had “left the ministry” and “gone into secular work.” Rejecting this “quasi-priestly concept of the ministry” he replied, citing all that he had been able to do while a professor for the church in its outreach to the university, particularly as Warden of Men’s Residences for fourteen years.

Like most Calvinists, Stanford Reid had a strong work ethic. While at McGill, in addition to his residence responsibilities, he was not only a member of the History Department and after 1963 a full professor, he was also chief invigilator and university marshal, being highly visible in academic processions at convocations. The outgoing warden of the men’s dormitories, who left him an administrative and disciplinary tangle, said that he qualified to be his successor because, not in spite of, his Christian commitment. Supervising exams and punishing those who cheated, called for a person of unimpeachable integrity. As he referenced in his 1976 commencement speech, members of the large Montreal Jewish community at McGill felt especially drawn to him. As he told it, they were also exemplary in their work ethic, knowing that they had to excel in their studies given the anti-Semitic discrimination they experienced.

Not so some of the Christian students. He was continually reminding them, and particularly members of the IVCF chapter, that they had an obligation and responsibility to be outstanding witnesses to Christ by the quality and integrity of their academic work. Too often, he claimed, they preferred prayer meetings to hard slog. In this concern he set an example. From the time his first volume appeared at the age of 23 (The Church of Scotland in Lower Canada, his master’s thesis at McGill) to his final book reviews written in 1996 from his shared and cramped room in a Guelph nursing home, he produced papers, articles and reviews on an amazing variety of subjects, expressing his wide range of interests. Some said he published too much material to maintain a high quality of scholarship but it was impressive. When his Economic History of Great Britain appeared in 1954 and became a college text he observed that he had new credibility as its publication secured his teaching position with his patron, McGill Principal Cyril James. Reid offered a serious warning to would-be Christian academics: ”The Christian professor, however, will have few if any graduate students to supervise unless he has something of a reputation as a scholar. In fact, one soon discovers that usually both undergraduate and graduate students check in the university library catalogue to see if the faculty member has published very much, before they take him and his views seriously.”[8]

One of the questions that surfaced at the Reid centenary colloquia in Montreal in 2013 is whether what Reid accomplished as a professing Chrisitan would be possible today. The number of unemployed (and one fears, unemployable) Ph. D.’s who attended suggests that it is a different era for academic historians, particularly those of Christian faith. Whether that reflects our culture today with its sometimes denigration of tradition, its apparent lack of regard for the past, is a moot point. Certainly the freedom Stanford Reid enjoyed to express his Christian faith in the classroom is a thing of the past.

At the end of the day, Stanford Reid’s legacy is that of a Christian gentleman. As he had throughout his life everywhere he lived, he led a Bible Study in his nursing home. As death approached, his notes for the study he led on the 23rd Psalm provide testimony to his faith: “The psalmist likens our redeeming God to a good shepherd, a position which Jesus claimed for Himself as the Son of God.”[9] In a reflection from my biography that has often been quoted since I wrote it: “Throughout his life he was frequently ignored, minimized, ostracized, even rejected. Remarkably none of these experiences left him bitter or angry. His Reformed faith provided a ready antidote to this buffeting. He was continually going back to the themes of providence and the perseverance of the saints. His Calvinism was of a very practical and personal nature.”[10]

[1] http://archon.wheaton.edu/?p=digitallibrary/digitalcontent&id=4806 accessed 8 September 2016.

[2] Marsden, George. The Soul of the American University. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994) 416.

[3] Holmes, Arthur F. The Idea of a Christian College. (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans), 1975. 80.

[4] See my “Machen and the PCC’s Andrew Grant’s 1925 Partnership to Save ‘True Evangelical Christianity’” and “Knox College and Knox Church: Going Separate Ways After Church Union” both on adonaldmacleod.com

[5] Reid, W.S. “A Presuppositional Interpretation of History” 10pp mss in my possession, page 1.

[6] Reid, W,S, “The Christian Professor in the Secular University” 9 pp mss in my possession, page 2.

[7] Stanford Reid to Alex MacSween, 7 September 1974. (University of Guelph Archives).

[8] “The Christian Professor in the Secular University” 10+3 pp in my possession, page 5a.

[9] “The Lord Our Shepherd” Study given at the Stone Lodge, 17 April 1995, In ny possession.

[10] MacLeod, A. D. W. Stanford Reid: An Evangelical Calvinist in the Academy. Montreal & Kingston: McGill Queens University Press, 2004, 300.