(Paper read to Presbyterian Scholars Conference, Wheaton College, 23 Oct. 2018)

- Finding the letter

Southern Presbyterian missionary to China Martin Armstrong Hopkins was finally able to return to his station in the spring of 1946. North China Theological Seminary (NCTS) [1], where he had taught before the war, was in ruins, abandoned now by the defeated Japanese. The thirty-two building campus had included lecture rooms, offices, a library, a chapel, faculty homes and servants quarters, the largest theological seminary in pre-war China. Hopkins had reconstituted the school further south into Kiangsu province to the city of Xuzhou. He was now returning, seven months after a so-called “peace” had been declared, on a salvage operation: books, furniture, whatever else had been undamaged. A year later even what had been left by the Japanese was destroyed as Chiang Kai-shek’s beleaguered army and the Communist Eighth Route Army chose the school site to do battle.

Hopkins made his way to what had been the home of Watson Hayes, the founder and president of the Seminary. Among other items of furniture he retrieved the hallowed desk that Hayes had used to prepare his lectures, write letters, and pursue his own devotional and scholarly interests. Hayes and his demented wife Margaret Ellen, both octogenarians, had been dragged out of the building by Japanese soldiers, the final Western missionaries to leave the compound, on 28 July 1943. The aged couple were forced onto a train to Weihsien camp, located on the site of the American Presbyterian Mission where they joined Eric Liddell and other missionaries along with 300 China mishkids from Chefoo Schools for the duration of the war. However, Watson McMillan Hayes, son of a Union army soldier who had been killed in battle, finally gave up the fight on 2nd of August 1944.

A year and a half later, in what remained of Hayes’ looted home in Tenghsien Hopkins found papers scattered on the floor. One item was a fragment of a timely letter disclosing that Watson Hayes was having a serious (and one assumes, confidential) theological conversation with Robert L. Speer, Secretary of the Board of Foreign Missions of the Presbyterian Church USA, a denomination riven by theological strife about the major theological issue of the hour, one of great and general concern: the nature of Biblical authority and inspiration. It was at the heart of a debate then raging among China missionaries of the PC(USA). As always, many preferred to fudge about the matter, finding it divisive and unhelpful, particularly on the mission field with its close network of relationships, Christians seeking to share the Christian gospel in an inhospitable and sometimes dangerous environment.

Of the sixteen PC(USA) mission fields there were undeclared but recognisable theological divides among appointees: Korea and Cameroon were for evangelicals, Japan and the Philippines for the more open and flexible in their theology. The China Mission represented the widest spectrum of all, from strict Calvinism, dispensationalism, and some influenced by contemporary theological liberalism. China had a large number of educational and medical ministries, attracting people with faith but little theology. The Southern Presbyterians in China were generally orthodox and warmly Evangelical. In 1938 the appointment of liberal Lloyd Ruland [2] as China Secretary suggested balance was abandoned.

- Who were the correspondents?

The letter was sent by Robert L. Speer, Secretary of the Board of Foreign Missions of the PC(USA His letter conveyed, even as a fragment, something of the warmly pastoral relationship for which Speer was known. Of all the Board’s 1500 staff only six predated Speer’s coming to the Board and with many he was on a first name basis, taking personal interest in their families and ministries.

Speer had an emotional attachment to China and the work of the PCUSA Mission Board there, possibly the most successful and most influential of all its fifteen fields and certainly one that had received much of its treasure, talent and attention. Since 1891, when he joined the staff of Board, he had made two major and lengthy visits there, curiously just prior to major political upheavals: in 1896/7 prior to the Boxer Uprising and in 1926/7, a time of civil unrest as Communists with Soviet support jockeyed for power with Chiang kai-shek and most missionaries fled the country. Missionary work in China was costly: the Baoding martyrs of 1900 were only some of the American Presbyterians who paid with their lives for their missionary service.

Speer had another reason for an emotional attachment to China: his daughter Margaret had gone out to Beijing in 1925 as a Board appointee. It had not always been easy for her. In 1930 she had been sent home by the North China Mission (much to her and her father’s annoyance) to requalify for reappointment by earning a graduate degree. Robert Speer wrote her: “It is not a good thing for our family to be setting the example of undercutting the regulations,”[3] Margaret Speer’s father set a high standard for relationships with the Board’s 1500 missionaries, as a person of integrity and faith and always scrupulously fair and even-handed.

Watson Hayes, must have been a particular challenge. Hayes had arrived in 1882 and was widely

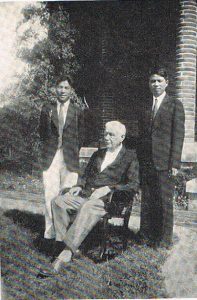

Watson Hayes with students, 1932.

known and respected for his brilliance and breadth of knowledge, a real Renaissance man. At Tengchow College Hayes taught astronomy, geology, physics, and mathematics, a first in China at that time. He became President in 1895. Seven years later the school joined with the English Baptists (and others) to form Cheloo Christian University in Jinan, capital of Shandong. It was not a happy union Hayes was particularly irked by a teacher who, in a chapel talk, held up the Old Testament to ridicule. Another missionary wrote that “The virgin birth is scoffed at, the bodily resurrection of Jesus Christ is explained away, and even the Deity of Christ is questioned by some of the foreigners on the faculty.” When Hayes resigned in protest, the students had taken drastic action. Harry Romig[4] recalled: “They were decidedly unwilling that [5] Hayes should no longer have a seat on the faculty bench. When they were not appeased, and little consideration given to their complaint, all nineteen students from the Presbyterian bodies walked out.” Watson Hayes was the hero of the Chinese church.

The establishment of the resulting North China Theological Seminary in Tenghsien was a catastrophe for his ecumenical sensitivities. It was compounded in 1927 when the Church of Christ in China, a long-time goal of Speer’s, was constituted without the Shandong presbyteries of the Chinese Presbyterian Church which continued its existence[6] as a strongly committed Reformed institution. Financially it was independent, having wide support among like-minded donors. It negotiated directly for faculty, enlisting my father, Princeton Class of 1928, to teach New Testament after one year of teaching history at Wheaton College and marrying his Wheaton bride..

Ruins Swarthmore Church’s NCTS Chapel. 1946.

What most bothered Speer was the fact that, aside from the Seminary being a huge success outstripping both the Yenjing and Nanking seminaries in enrolment and as well, independence from foreign influence, though challenged fiscally during the early Depression years, NCTS was financially independent. This came primarily because of Winston Hayes’ ability to appeal to wealthy donors, particularly in Philadelphia Presbytery and specifically in Swarthmore Church, members of whom built the , beautiful; 400 seating capacity chapel in memory of a former interim pastor. He also assembled an impressive faculty from the Chinese church, dispelling the racist myth that so-called “fundamentalists” were ignorant foreigners seeking to impose their craziness on gullible Chinese.

- The year 1933 in the PC(USA)

The fragment was dated 8 June 1933, a Thursday. The General Assembly a fortnight earlier had met in Syracuse in the heart of the Finney-ite, New School, so-called “Burnt-over District.”. That date says a lot about Speer’s legendary work ethic. The Assembly had convened on Thursday, 26 May, and a fortnight later he was back at his desk in his Manhattan office dictating letters. Speer had an almost avuncular relationship with many, if not most, of his staff who were passionately loyal to him. Of the Board’s 1500 employees only six now predated his coming to the Board. With many he was on a first name basis, taking personal (and pastoral) interest in their lives and families.

“One Century Past, Another to Come” was the theme for Assembly that year, a recognition that 1933 marked the centenary of the Mission Board and the impending retirement of its Secretary. In all its one hundred years there had been only two general secretaries at the helm, a remarkable record Speer, now on the way out, had taken over from John C. Lowrie. Lowrie, an 1833 Princeton Seminary graduate had, after brief service in India and the death of his wife, had returned to America and joined his father at the Board office when it was set up. He was formally appointed in 1850 and stayed for forty-one years. He died at the age of 90 having handed over the responsibilities of office to Speer as well as an opulent new Art Deco office building on Manhattan’s Fifth Avenue.

The denomination had chosen both secretaries to be the moderator of General Assemblies in troubled times for the denomination: Lowrie in 1865 after a Civil War and a country and a church divided north and south, Speer in 1927 as the compromise sole nominee in a church increasingly riven by theological controversy. Speer emerged from his year as moderator with a pending reorganization of Princeton Seminary, the training school for many foreign missionaries with an inevitable impact on the Board. As a close friend of Princeton Professor Charles Erdman and as an acquaintance of President Ross Stephenson he developed a visceral hatred of Professor J. Gresham Machen. Machen had left Princeton Seminary as a result of its reorganization for which his friends attributed some blame to Speer. On 11 April there had been a fractious debated between Machen and Speer in Trenton (NJ)’s Fourth Presbyterian Church, sponsored by the Presbytery of New Brunswick, in which both sides claimed victory and vindication.

That year 1933 the blows kept coming: first the Hocking (“Layman’s”) Report Rethinking Missions, then the Pearl Buck debacle. Those two events, and the lack of a credible response by Speer, led inexorably to schism and separation. Foreign missions, which had once united the church in a common commitment, was now proving divisive, In rapid sequence one disaster seemed to be followed by another. Speer was a beleaguered man when he wrote Hayes and must have inevitably identified Watson Hayes as another hectoring separatist, a founder with his enemies of a rebel theological seminary in China whose influence had affected the merger of the Church of Christ in China, which he regarded as one of the great achievements of his life.

Then, to compound a difficult situation, there were reports of an Independent Board of Presbyterian Foreign Missions, founded by his nemesis J. Gresham Machen. On 28 May 1933 the Syracuse Herald had a full page spread about the Assembly on 26 May[7] in which it reported: “Dr. Machen and his associates on the Independent Board of Missions [sic] [are] charged with insubordination in refusing to resign from the board, will know their fate during the Assembly meeting. The Permanent Judicial Review Commission is reviewing their appeal from orders of their Presbyteries suspending them from the ministry, and will report to the Assembly which they will vote on without debate.” Needless to say, the vote went against them and Machen and his friends were expelled from the ministry of the denomination.

- Speer the theologian on inspiration

It is significant that Speer, who was never ordained and had dropped out of Princeton Seminary after his first year to join the Student Volunteer Movement, resorted to theological distinctive in his letter to Dr. Hayes who was no slouch theologically himself. As a student of Warfield while at Western Seminary, Speer was speaking directly to Hayes’ background which he knew well: on familiar territory for Hayes. But it was specifically Warfield’s view of the sacred text that Speer challenged, pitting Warfield against traditional Reformed orthodoxy:

(a) Warfield got it wrong: we have no inerrant Bible

` Speer began with a direct attack on B. B. Warfield, taking direct aim the professor who, more than any other, influenced Hayes in his theological studies at Western Seminary ( (1878-1881) and set NCTS’ commitment to verbal plenary inspiration during the brief time that Warfield taught there before going to Princeton Seminary. He begins: “It would have been a good thing for all of us and it would be a good thing for all of us if we were still to adhere faithfully to the institution of the Church, The trouble is that so many have not done so, Dr. Warfield did not do so. He set the example of the interpretation of the first chapter of the Confession of Faith wholly at variance with the mind of the Westminster Assembly.That Assembly had present to its mind the present-day concept of the inspiration of the original manuscripts as this idea of the inspiration of the original manuscripts different from the inspiration of our present Bible and it repudiated this idea absolutely.”

What Speer appears to be saying is that we do not have the original (inspired) text so why quibble about an infallible and inerrant Bible? It doesn’t presently exist. But then he throws down the gauntlet:

(b) ‘Friends’ in the home churches also got it wrong

Not only was Warfield misguided, the simple believers in the home churches also were misguided. They don’t have an inerrant Bible either.

”I think that these friends in the Home Church who have been contending for the verbal inerrancy of the original manuscripts as contrasted with our present Bible have been playing with fire.”

Many of those who had given sacrificially for the work of the Mission Board or put their lives on the line for the propagation of the gospel would not have been satisfied with this – in their mind – evasion.

(c) Francis Landey Patton was right: Mt. 27:9 makes inerrancy impossible

Speer then goes on to pit Francis Landey, who at different periods was president of both Princeton University (he renamed it) and Princeton Seminary.

` “I think Dr Patton’s position adverse to Dr. Warfield’s is impregnable, when he refuses absolutely to attach his faith and the inspiration of the Bible to the doctrine [8] of verbal inerrancies of the original manuscripts. There is just as much evidence that Matthew 23:13 (sic) is a part of the original manuscript of Matthew as it is that Matthew 11:25-30 is original and yet the quotation in Mathew 23:13 (sic) is not from Jeremiah but is from Zechariah and it is not a verbal quotation., I think that we have got to come to the Bible account of itself and to the pure Westminster Confession doctrine which holds that the same spirit (sic) that gave the Bible has preserved it.”

Patton’s Inspiration of Scripture was a text in theological seminaries of the Reformed faith for half a century. In checking several of the various editions of this classic text I find no reference to Matthew 27:9 which is presumably the verse that Speer means, not Matthew 23:13. The only other possible reference might conceivably be to Patton’s florid encomium on the death of Warfield in the Princeton Theological Review in which Patton extols the need for private judgment and surprisingly hedges Warfield’s view of inspiration with qualifications.[9] His use of Patton to support his arguments cannot be substantiated and appears spurious.

- Conclusion

In the meantime Watson Hayes and his colleagues seemed energized by the establishment of an independent board. Albert Baldwin Dodd[10] who was a close colleague of Hayes from the initial establishment of the Seminary, having come to China in 1902, resigned from the PC(USA) Mission Board and aligned himself with the Independent Board. On 17 August 1933 Dr. Hayes wrote a personal letter to Machen. He had read of the establishment of a new mission board in Christianity Today and was appealing to that Board for financial assistance. “Hitherto,” he explained, “this seminary has not asked nor received any money from the P.B.F.M. [Presbyterian Board of Foreign Missions]. At first we were notified in advance that it would not be given, and later, when asked to present an estimate, we decided not to do so, lest in doing so might sooner or later, receive a Modernistic teacher assigned here.” What a reflection on the state of the denomination. Watson Hayes was committed to a theology that was at variance from the one that Robert Speer found himself sliding into, a denial of the absolute trustworthiness, authority and inspiration of an inerrant Scripture. His old professor, B. B. Warfield, would have been proud of him and the leadership he and his Seminary exercised in the young Chinese church.

Indeed seminaries do shape faithful ministries. It is claimed that NCTS’s strong commitment to Reformed orthodoxy set the tone for the Chinese church in the years following Communist “liberation.” The Seminary may now be a ghost of the past, its beautiful campus replaced by the North China Flour Mills, but its testimony to the Bread of Life through the faithful leadership of Watson Hayes lives on.

[1] On NCTS see Yao, Kevin Xiyi, “NCTS: Evangelical theological education in China in the early 1900s” in Kalu, Ogbu Ed.. Contemporary Christianity: Global Processes and Local Identities. Grand Rapids, MI 2008, 185-206.

[2] Lloyd Stanton Ruland (1889-1953) Graduate Westminster College, 1912 (DD 1932), McCormick Seminary, 1916. Decade with PC(USA) in Shandong. Returned to US in 1926 and pastored West PC(USA) Binghamton, NY until 1938 when appointed Board Secretary for China, leading a delegation there in 1946

[3] Piper, J.T. Robert E. Speer: Prophet of the American Church. Louisville, KY:Geneva Press, 2000, 178.

[4] Harry Romig “Early History of North China Theological Seminary” handwritten in 1946 and transcribed by A. N. MacLeod. (Author’s archive)

[5] E. C. Lobenstine to Walter Lowrie 21 August 1921 (PCUSABD RG82, 20-13).

[6] See G. Thompson Brown’s Earthen Vessels and Transcendent :Power: American Presbyterians in China, 1837-1952. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1997, 212-213.

[7] https://newspaperarchive.com/syracuse-herald-may-26-1936-p-10 (accessed 17 October 2018)

[8] W. M. Hayes to J. G. Machen, 17 August 1933 (Machen Archive, WTS).

[9] Patton, F.L. “B. B. Warfield: A Memorial Address , Princeton Theological Review, July 1921, 1-2

[10] Albert Baldwin Dodd (1877 – 1972) gave the commencement address at WTS in 1936.